I often find myself frustrated by much of the dialogue that surrounds teen girls as it can in fact be very damaging. Sadly, those that use these assumptions and stereotypes are often those who may well have girls’ best interests at heart, but are possibly unaware as to how harmful the messages they are delivering really are.

I asked a number of leading feminists and educators to set the record straight for us and ensure that when we aim to support girls, we don’t inadvertently matters worse for them. Over the next few weeks I shall share their responses.

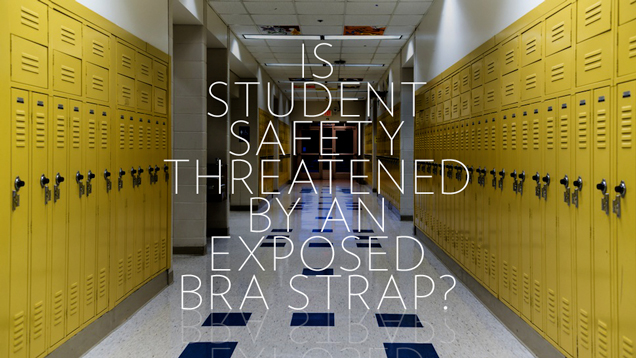

1. Skirt length = a measure of morality

The policing of the way teen girls wear their school uniform really concerns me. Whilst uniform guidelines are fine and part of life for both genders, framing these in terms of morality is not. So many teen girls tell me they have been told things like: “You’re a good girl, but that skirt length sends off the wrong message” , or “You’re distracting the boys…”. This is the slippery slope that excuses the harassment of girls based on their clothing choice and ultimately may lead them to feel shame about their bodies ( an idea I have explored before here). Author, columnist and academic Dr Karen Brooks agrees:

I think what bothers me most about this whole uniform and clothing issue is that somehow, female clothing has become a visual barometer that measures a woman/girl’s morality and ethics and somehow also controls men’s. That’s why claims that if a man or boy is distracted/loses control/rapes/abuses/harrasses etc. then it’s the girl/woman’s fault carry weight in society. We still somehow believe that a woman’s dress indicates her morality and invites or rejects (male) attention. Well, if that’s the case, why is that women and girls who wear hijabs or dress in non-revelaing clothing are still raped/attract unwanted attention/harrassed and are also held accountable for male behaviour when it is transgressive and/or violent?

Teachers surely know it’s not the short skirt that warrants changing, but antediluvian attitudes that let males off the hook.

It’s the Damned Whores and God’s Police model all over again, yet what girl’s are being told is that what they wear is a way of modifying, “policing” male behaviour and their own sexuality as well. There is a false notion circulating that women can control men and keep ourselves “safe” by our clothing choices. What utter nonsense.

Clothing is not the issue. Society is. Yes, we need to take responsibility for our behaviours, regardless of sex. As long as we allow men and boys to shift blame for their choices, for their harassment or worse of women, nothing will be resolved. Clothes do not maketh the woman, but actions maketh the man (and woman)!

Feminist web site jezebel recently published a thought provoking piece, “Is Your Dress Code Sexist? A Guide.” This paragraph particularly resonated with me:

Look: I understand the desire a school might have to encourage students to dress respectfully and semi-professionally; out-of-the-ordinary or extreme clothing is distracting on a purely asexual level. Could you study next to a guy in a clown suit? Or a woman wearing an enormous Pharrell hat that plays music? I couldn’t. The key is to make it clear that both men and women need to adhere to any rules put in place, and that the rules are to ensure student focus is on the instructor rather than on other students.

And the reality is that no matter how careful an organization is to make sure they don’t sound …sexist…, women have more at stake in adhering to dress codes than men do, because women’s fashion dictates that women must wear less in order to be fashionable. Girls get so many sets of conflicting instructions that they’ll be punished by either their peers or their school no matter what they do. Wear revealing clothing, or you’re a dork, says the media to women. Don’t wear revealing clothing, or you’re a slut, say institutions to women. Talk about distracting.

When I asked her for her input, journalist Tracey Spicer said she thinks it is also important for us to honestly reflect on how we dressed as young women too:

What I really hate are the casually sexist comments about how young women are dressed for a night on the town. All this ‘They look like hookers!’ and ‘They’re asking for it’ stuff. For goodness sake, I used to dress in revealing outfits at that age, as I was discovering my sexuality. That doesn’t mean I’m asking to be sexually assaulted.

2. Mean Girls

Social commentator and writer Jane Caro wishes we would question the rhetoric around girls as “mean girls” :

The idea that girls are bitchy and nasty to one another, whereas boys are simple creatures who fix things with a good thump (?).

We expect women to tend relationships, to do the emotional care taking, girls know this but when they are young, they’re just learning about relationships and they do them badly. Instead of congratulating them for taking on this difficult and complex task (understanding how people relate to one another), we jump all over them & stereotype them as mean girls. This drives me nuts! I also hate the moral panic around ‘bullying’, which often ends up with us bullying the supposed bullies. We need to be much clearer about what bullying is and what it isn’t, and that most kids are both victims & perpetrators at various times. As are we all.

It is the first point Jane raises that was explored at the Festival Of Dangerous Ideas session entitled All Women Hate Each Other. I was privileged to speak at this alongside the truly awesome Germaine Greer, Tara Moss and Eva Cox. You may watch this session here: http://play.sydneyoperahouse.com/index.php/media/1654-All-Women-Hate-Each-Other.html

Melissa Carson, the Co-ordinator of Innovative Learning at boys’ school Oakhill College also believes the boys-as-less-complex creatures myth is dismissive of the complex nature of mate-ship and equally as damaging to boys: “I’ve worked closely with young men for over ten years and I can tell you they do stew on their friendship fall-outs. They report feelings of sadness, anger and frustration over their friendships and often don’t know how to resolve things. They are every bit as complicated as young women and in need of just as much support.”

3. One mistake and you’re out!

The “one mistake and you’re doomed” approach to educating young people drives me insane. I often hear this in the context of cyber training; messages like: “If you ever post something on Facebook that’s not ideal, you’ll never be employed and will be socially shamed. And you will never be able to make that go away.” Implication? You may as well give up now if you’ve done something silly as you can’t ever make that right. Sadly, it is messages like this that lead young people to despair and to want to hide their errors for fear of being judged. Incidentally, I often wonder just who will be employed in the future if this was in fact true as I can’t imagine there will be anyone who hasn’t at least done one thing on-line that wasn’t smart at some stage in their youth. Again, Dr Karen Brooks agreed:

As for the cyber mistake. Oh puhleez! Yes, we need to educate young people that what they post could be potentially damaging and may impact in the future, but when and if they do post something inappropriate, we should also rally to ensure they understand that they can overcome this. In fact, understanding you can move beyond the inappropriate photo or posting can not only build resilience, but instil valuable lessons in how to cope with negative feedback, distressing reactions, how to negotiate an emotional and psychological minefield, but also how important it is to own what you’ve done/posted. Take responsibility and learn from it and move on (nothing to see here!). If it hits you in the face in later years, then take responsibility again, but also contextualise it and demonstrate how much you grew from that moment and what lessons you took away from the (bad and silly) experience to become the person you are now.

Yes, we catastrophize to ours and the kids’ detriment. So much for resilience, we’re teaching them to fall apart at the first mistake and to cry “my life is over!”. Ridiculous!

Author, speaker and advocate Nina Funnell concurred:

The most dangerous thing we can ever say to a young person is that there is no way forward, no light at the end of the tunnel, no possibility of recovery. And yet this is exactly the message they hear when we tell them that once you post something online, it is there forever, the damage is permanent and will never lighten. If a young person has made a mistake, catastrophising the situation will only lead to catastrophic outcomes and already we have seen one case in America where a teen took her life following a school seminar which reinforced the notion that she could never get a job or a university degree since she had already made an online mistake. Instead of this doom and gloom approach, we need to help teens develop resilience, the strength to overcome setbacks, and the insight to be able to put their mistakes into context.

More things we need to stop saying to girls NOW next week. In the meantime, I’d love to hear from you. What messages do you think we deliver to young women that are harmful?