The books we read have an incredible power to shape our thoughts, and our view of the world and our place in it. Fiction delights, enthralls, infuriates, inspires. It transports us to other realities. Sometimes we escape into it for entertainment and relaxation; other times we seek out books that stretch our minds beyond our boundaries. A few simple words on a page can bring us to tears — or provide the deepest kind of solace. Books raise questions that only we can answer for ourselves; they pose dilemmas that nudge us to reconsider our own beliefs and attitudes.

All of this is especially true for children, who are still forming their identities, still getting to know who they are — and most importantly, everything they can become.

That’s why I love the picture book Ruby Who?, which is the brainchild of a talented Queensland woman, Hailey Bartholomew. She came up with a creative way of explaining to her two daughters that “wishing to be like others, or have what other people have, can be a trap and will not make you happy”. She got together with her friend Natala Stuetz and made a short film, which has since been made into a primary-school-age picture book illustrated by Alarna Zinn.

That’s why I love the picture book Ruby Who?, which is the brainchild of a talented Queensland woman, Hailey Bartholomew. She came up with a creative way of explaining to her two daughters that “wishing to be like others, or have what other people have, can be a trap and will not make you happy”. She got together with her friend Natala Stuetz and made a short film, which has since been made into a primary-school-age picture book illustrated by Alarna Zinn.

Ruby is a little girl who “wishes for so many things and dreams of being like others”. That is, until she goes on an adventure and rediscovers her own identity, and the joy of just being herself. Hailey says:

Ruby Who? was created as a way to explain to children that having more ‘stuff’ doesn’t make life better; looking like the other kids won’t make you happy; it’s who you are when you’re being yourself that counts.

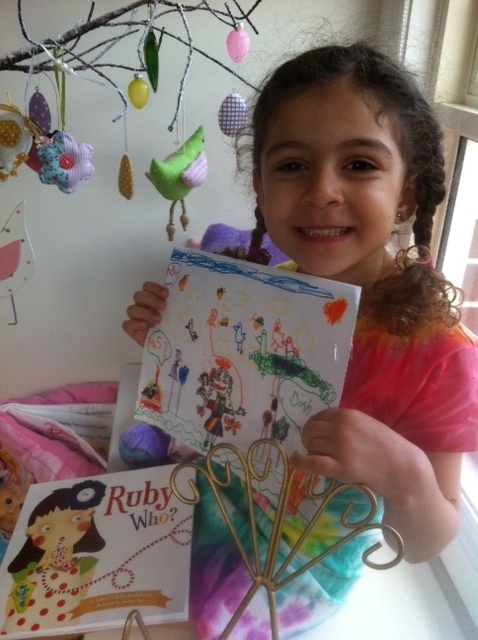

What makes Ruby Who? such a special book is that not only does it have an awesome message, it’s very cute and colourful, filled with playful rhymes, and kids love it. I asked Francesca Kaoutal, Enlighten’s co-founder, to read it with her 5-year-old daughter Bianca. This is Bianca’s review (which is also very cute!).

I like Ruby. She has lots of colours like me. She is funny with her rolly shoes. You can’t jump in rolly shoes. It’s a good idea that she took them off. She goes on swings and I love swings and jumps and playing outside with the birds in my rainbow and sparkle clothes. I love the picture of the sausage dog because it is so silly. Sausage dogs don’t have hats and balloons! That is so funny. It is a good picture for laughing.

There are a host of great books for tween and teen girls, too, and I am looking forward to reading two that were just highly commended by the judges of the Barbara Jefferis Award: Kelly Gardiner’s Act of Faith, and Meg Mundell’s Black Glass. The Barbara Jefferis Award is worth looking out for each year, as it bestows a prize for “the best novel written by an Australian author that depicts women and girls in a positive way or otherwise empowers the status of women and girls in society”. (This year’s winner was Anna Funder’s All That I Am.) Act of Faith will especially be embraced by girls who love history and books. Set in 1640, its heroine, Isabella, flees Oliver Cromwell’s England and discovers a whole new world of possibility in the publishing world of Venice, “where women work alongside men as equal partners, and where books and beliefs are treasured”.

There are a host of great books for tween and teen girls, too, and I am looking forward to reading two that were just highly commended by the judges of the Barbara Jefferis Award: Kelly Gardiner’s Act of Faith, and Meg Mundell’s Black Glass. The Barbara Jefferis Award is worth looking out for each year, as it bestows a prize for “the best novel written by an Australian author that depicts women and girls in a positive way or otherwise empowers the status of women and girls in society”. (This year’s winner was Anna Funder’s All That I Am.) Act of Faith will especially be embraced by girls who love history and books. Set in 1640, its heroine, Isabella, flees Oliver Cromwell’s England and discovers a whole new world of possibility in the publishing world of Venice, “where women work alongside men as equal partners, and where books and beliefs are treasured”.

Black Glass is more for the girls in your life who love science fiction or gritty fantasy. A work of speculative fiction, it follows two resourceful sisters, Tally and Grace, as they make their way through a dystopic future urban landscape.

Black Glass is more for the girls in your life who love science fiction or gritty fantasy. A work of speculative fiction, it follows two resourceful sisters, Tally and Grace, as they make their way through a dystopic future urban landscape.

Some people dismiss the books that are the most popular amongst teen girls at the moment, picking apart the literary value of series such as The Hunger Games (Suzanne Collins) and Twilight (Stephenie Meyer), not to mention the slew of vampire-themed books that the latter has inspired. But is it really our job to be the arbiters of taste? As I’ve discussed on this blog before (in relation to Twilight and The Hunger Games), I think that no matter what our own taste in books may be, we should try to celebrate the books the teen girls in our lives decide to read. Rather than being judgmental of their reading choices, let’s just get them reading! I find it heartening to see so many young women reading these series passionately — and deconstructing not just the books, but their worlds, as they go. And let’s not forget that girls have wide-ranging tastes.

When I was a teen girl, I became obsessed with the Sweet Dreams series of novels, which were like Mills and Boon for teen girls. My favourite was P.S. I Love You. I thought the author’s play on words (the P.S. also stood for Palm Springs, where the book was set, and for the name of the main character’s love interest, Paul Strobe) was literary genius! And oh, how I howled at the end when Paul died of cancer.

Yet during the same period, I also devoured Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale, a speculative fiction that was a chilling social critique of totalitarianism and the backlash against feminism that was gathering force in the 1980s. It was a complex, thought-provoking book that was, and still is, considered a literary masterpiece.

Today your girl might be devouring a bodice-ripping vampire romance. Fight any urge you may have to roll your eyes, because it really is okay — and anyway, tomorrow she might be deep into Jane Eyre. There is a book for every mood: sometimes we read primarily for a momentary escape, other times because we want to engage in the world of ideas. But no matter what, let’s keep reading!